Since childhood I have always enjoyed mystery stories. I owe this love to my sister Carol who had a wonderful imagination.[1]

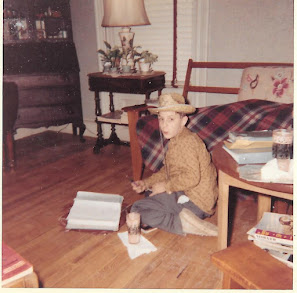

At night, when I was very little, I used to crawl into her bed and snuggle in with her. She was 6 years older than I was. So, she would have been around 8 at the time. I would have been about 2 – probably like a little animated doll to her. She would light up and the artistic wheels would start spinning in her brain and she would create on the spot the most wonderful mystery tales featuring Joe Pooh, the Teddy Bear Detective, full of high adventure, breathtaking escapes, puzzling enigmas.

She appears to have accessed A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh for the surname of this sleuth, but the rest of the tales were all her.

Eventually, we’d both doze off and our frustrated mother would find little me spread all over the bed in the morning and poor Carol clinging to the far side all but falling off. My mom would order me to stay in my own bed and let my sister get her rest. But the lure of adventure with Joe Pooh was irresistible. What would this intrepid detective face next?

The memory of her love and her watch-care for me and her wonderful stories and all the adventures she created in real life for me and my friends – these were her legacy to me . And they formed the basis for my egalitarian views today, that women can do anything. Because, my sister could do anything. She was my model of the gifted, accomplished go-getter.

But my admiration for my sister was so strong I never imagined myself competing with her. She was my champion with my parents, sweet-talking them into sparing me from my foibles and I am still filled with indelible memories of her gracious care for me over 70 years later. Until Aída came along, I never met anybody I loved like I did Carol.

One strong follow-through was that, as early as second grade, I began to write very simple little stories. Soon I had created my own detective, Mike Macdonald, who stared in such stories as “Mike Macdonald and the Leaky Tube Mystery” and “Mike Macdonald and the Exploding Pop Bottles.” They were pretty miserable tales. Hardly up to the quality of what my sister created. The epitome of my youthful excursion into suspense was a 50 or so page potboiler I called “Fool’s Mate” (I had been playing chess with my dad). All I can remember about it was that, at the climax of the story, my detective escapes by opening a tin foil gum wrapper and flashing the blinding sun’s reflection into the eyes of the thug, holding him captive. After that dismal incident, I moved over to sci fi in what was then called junior high with a tale entitled “Invaders from the Ninth Dimension.” My English teacher actually liked it and gave me a little praise for it along with an A!

That confirmed me in wanting to become a writer. But I never lost my love for the mystery genre. My loyalty to it carried on through me doing my doctoral dissertation on how the sacred Mysterium became the secular mystery, which I illustrated by critiquing the tales of the rabbis, ministers, priests, missionaries, etc. who, when the police are baffled, step in and with God’s perspicacity solve the crime.[2]

Thanks to Jeanne DeFazio, who put me in contact with the Southern California Motion Picture Council, one of her many, extensive Hollywood contacts, and due to Jeanne’s urging to enter one of their competitions, I won a prize and Jeanne won one too! My entry was my first published novel, an offbeat mystery called Name in the Papers,[3] a title I adopted from the old parental advice all us erring off-spring used to hear from our folks: “Just don’t get your name in the papers.” In my novel, all the major characters get their names in the newspapers!

Now, why have I told you all this about my sister and mysteries? Casual readers may not realize it, but the story of Job is set up as a mystery. And Job could be seen as a prototype of the hard-boiled detective. In this modern genre, the sleuth regularly gets beaten to a pulp, but constantly presses on with one goal—to see justice be done. For Job, the pain is hyper-spaced! We may even say that Job fits in a sub-genre in mystery literature: the courtroom procedural. And let me tell you something else: Job’s book is not the only instance of the mystery appearing in ancient Jewish literature. In the Apocrypha, the collection of books written between the end of the Old and beginning of the New Testaments, the stories of Bel and the Dragon and Susannah are rip-roaring mystery tales. Susannah, particularly, is set up similarly to Job as a felony trial.

What is paramount to me in Job’s account is the pain. I can hardly imagine the hours of grieving silence that Job experienced in the all-at-once loss of 10 children. The pain of this catastrophe is heart-rendering.

In Job’s narrative, we don’t see the birth of each child and the joy of Job and his wife as they nurtured each little son and daughter. We only see these children as adults in each other’s homes. But, they must have gotten a lot of love from Job and his wife, for, according to Job 1:4 and 13, they were bubbling over with good will, making sure all their siblings were included, as they all partied together during festivals. They loved each other and I’m sure they loved their mom and their dad very much.

With such an exuberant family, Job was a good, watchful dad. The morning after their celebrations, Job would always do a purifying ritual for his kids, sacrificing to the Lord God, just in case the humor got out of hand and they were disrespectful to God. Verse 5 in chapter 1 tells us Job did this all the time. Look how he loved his children.

Now, Job sits in the dust, crushed, miserable, grieving for the loss of his family and everything that was his. He’s taken the buffeting of bad news one by one without comment, but, notice, verses 1:18-20 tell us, when he learns that his precious children are all dead that’s when he rises up, tears his clothing, shaves off his beard, and falls to the ground before God.

Job has no idea why all this is happening to him, but he throws himself before the Lord and blesses God’s name in 1:20-22.

As readers, we, of course, have the back story in chapters 1:6-12 and 2:1-6.

Unknown to Job, he’d become a victim to the conniving of the great opponent to all the good God does. Lucifer, the beautiful angel, now known as Satan, whose name means the Adversary in both the Hebrew of the Old Testament and the Greek of the New Testament. Satan had lost the proper respect for God and was now God’s opponent. Lucifer, as his name had been, had misused his own free will and was going abroad across the entire earth polluting the free will choices of the human beings whom God created to love.

As God’s nemesis, Satan confronted God one day. The goal was to destroy the human being with whom God was most pleased in order to prove God wrong about humans. If God abandoned humans, they would become Satan’s victims completely.

So, given this challenge and its dire consequences, why does God allow Satan to try?

We aren’t told. Maybe God was still holding out hope that Satan might repent himself when he saw the steadfastness of Job’s commitment? That seems a bit far-fetched since God knows everything and Revelation 20:10 tells us ultimately God will destroy Satan. So that theory seems unlikely.

More likely, God is choosing Job to illustrate to all humans that, in our fallen world, we should expect disaster to come, but we should model ourselves on Job and persevere in our commitment to God and trust God will deliver us either here or in the age to come.

Some, of course, might simply see this as the way ancient conflict was often resolved without huge loss of life. Satan has challenged the loyalty of humans to God. The proof or falsehood of this claim falls on an agreed-upon representative champion: the soon to be hapless Job. The challenge is: Will he be able to stay loyal to God, or will he turn, curse God, and fail?

Why ever God went along with Satan’s pernicious challenge, we can only infer.

In the meantime, for Job, one calamity after another besets him as Lucifer does its best to destroy Job’s faith.

Chapters 1 and 2 in Job’s book show us Job’s depth of misery.

In addition, Job’s wife is always seen as the bad femme fatale in our reading of this story. She blames Job for everything. Of course, in her culture losing a child – in this case all her children! – is seen as a curse itself from God. She has been completely disgraced, plunged to the depths of the social order. She is bereaved and furious at the same time at this destruction of her home, her family, and her reputation, none of which she deserved. She’d done nothing wrong either. She is not even counted within the challenge. She is collateral damage, another innocent bystander, like Job, whose life has been shattered by the war in heaven.

Since I lost my wonderful sister when I was six years old, and was left as an only child, I try to understand the emotional pain that Job’s wife was experiencing. Notice, God never reproves her but is apparently content with Job’s simple retort not to be foolish, good and trouble are the lot for fallen humans and God is still in control.

With Job, although he has nothing now to do, because he has nothing to do it with, he finds his hands are still full because he is burdened with sores and this horrible puzzle of why all this happened to him.

Since he’s in a mystery, because he has no idea why he is going through these disasters, today his ordeal would be classified as a “fish out of water” tale. In this sub-genre of mystery literature, our hero or heroine is thrown into a situation that she or he can’t fathom. The task is to uncover what is happening and why.

We readers would like to help him, but we can’t. We just stand by helpless, watching him try every angle to get through to the truth.

In Job’s case, all he can see is that he is a righteous person being prosecuted as a felon. To underscore this theme, legal language and incidents move this account along.

Job’s trial starts with a charge being levied against his integrity brought by the plaintiff Lucifer who includes in his deposition a smirch on God’s character for nepotism (that is, showing favoritism toward Job [Job 1:9-10]).

Next, a trio of witnesses, supposed to be for the defense, but sounding like they’re for the prosecution, hold forth, accusing Job of all kinds of malfeasant actions. Interesting to note is that the first witness in chapter 4 has been influenced by the plaintiff Satan, through a vision and spiritual forms appearing in his sleep, and a “still voice” imitating God’s which together make the witness accuse Job of being foolish (5:2-3). He even charges him with being responsible for the death of his own children (5:4), and he accuses him of other crimes and shortcomings needing correction from God (5:17-18). This is called tampering with a witness and it is illegal today. Of course, illegal is what Satan regularly does. It’s his m. o. So, no shocker there!

Job, as his own attorney, must have astonished everyone when he asks for the death penalty in 6:8-9. Not a surprise to us, however, because he had been contemplating this sentence in chapter 3:11-22. God, however, does not allow that option.

So, Job proceeds to insist his cause is just in 6:29, hence the title of our blog: “The Case of the Innocent Bystander.”

Job’s language is that used in trial transcriptions. In 9:14, Job talks about choosing out his arguments to present his case. In 10:2, he refers to God as his judge and, in 23:7, attributes the ruling of a verdict to God, asking God not “to pronounce, declare guilty, condemn [him] as guilty.”[4] The Hebrew term Job uses here, rasha‘, also means “lawless.”[5] In other words, Job is defending himself, arguing against being condemned as violating God’s law.

Then, finally, as Job rests his case in 31:40, a new human voice speaks in chapter 32, a young man (Job 32:4), named Elihu, who’s been listening in. He’s angry at Job and all three of his friends. Having listened to everyone’s speeches, he reproves Job for justifying himself and not, at the same time, justifying God (Job 32:2).

So, Elihu is challenging whether Job is actually a completely innocent bystander, as Job claims. He’s accusing Job of a sin of omission, meaning he blames Job for what Job hasn’t done: defend God’s justice along with his own innocence. Job does not disagree.

Elihu also rejects the views of Job’s friends because they condemned Job without any proof (Job 32:3).

Since Elihu is human and defends God as just, I see his role similar to that of a bailiff calling a court to order, because he is insisting divine justice be upheld.

What can we learn so far from the first 2 chapters of Job’s intriguing book? Here are my thoughts:

1) For starters, I think we can all agree that cursing God and dying is not an option, right?

Some of the experiences we have in life are truly miserable. But, if we reject God and die, we are not choosing to alleviate our troubles by resting in God’s everlasting arms. What’s the alternative destination we’ve chosen? Falling into Satan’s claws, which already have been making us all miserable. Look what happened to Job. So, a choice against God and toward Satan would be beyond dumb. Abysmally stupid doesn’t even begin to cover it.

2) Next, Job puts everything in perspective in chapters 1 and 2, when he says in effect in 1:21, “I started with nothing and I end with it. God gave me all I had and God removed it.” And he blesses God’s name.

One thing he does not say is: “I wish I’d spent more time with my children.” He doesn’t have to waste his energy in regrets for being an absent dad. He was there! He even showed up after their parties to cover any possible sins with sacrifices. Job seems to have lived what Peter recommends in 1 Peter 4:8: “Above all, to each other earnestly be giving love, because love covers over a quantity of sins.”

What is Job showing us from his example? Love your loved ones while you have them. Children don’t live forever on this earth. Neither do parents, or friends. Let those closest to you know that you love them right now. There may not be a later…

3) Sometimes in life we do feel, as Job did, that we are on trial. We ask, “Why me?”

Uptown Saturday Night is an urban comedy movie Aida and I enjoyed especially when we were ministering in Newark. In the movie, two friends go to a gambling den without their wives’ knowledge and get robbed. Desperate, they seek out a shady detective who absconds with the down payment they paid him to recover their stolen items. When they catch up to him, one of the victims, portrayed by Sydney Poitier, complains, “I trusted you…why me?” The detective, played by Richard Pryor, simply looks him square in the face and snaps, “Why not you, brother?”

When our first parents chose against following God’s will, this became a why-not-you-brother-and-why-not-you-sister? world. Scams and corruption, illness and disaster are one’s daily lot. This is a truth the great hymn “Amazing Grace” recounts: “Through many dangers, toils, and snares, I have already come.” The blessing is in the next two lines, “‘Tis grace hath brought me safe thus far, and grace will lead me home.”

4) So, this leads to our final application: Grace is what shores up Job, because it shores up all of us who believe. When many are abandoning Jesus and Jesus asks if the disciples are going to join this desertion, Peter, again, speaks for all true believers: “Lord, to whom would we go? The words of eternal life you have” (John 6:68-69).

As Paul encourages the Church at Corinth, in 2 Corinthians 4:17, our suffering here is temporary, but the glory which God has in store for us is eternal.

Job may think he no longer has any hopes for this life, but he does what Peter and the disciples did and what Paul encourages the Corinthians to do: he perseveres.

But what about his three friends? Are they getting a raw deal here? Elihu works them over, but is he right? Does God agree with him?

Next month we will continue studying the saga of Job, Aída is going to explore this crucial question, “What is good advice?” and we’ll find out.

For now, our case is in continuance…

Bill

[1] Adaption of a sermon on Job 1-2, preached at Pilgrim Church, Beverly, MA, Aug. 20, 2023.

[2] William David Spencer, Mysterium and Mystery: The Clerical Crime Novel (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1989).

[3] William David Spencer, Name in the Papers: 11 Snapshots and a Video (Levittown, PA: Helping Hands Press, 2013).

[4] A. Philip Brown, Bryan W. Smith, A Reader’s Hebrew Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 1274, note 5.

[5] Karl Feyerabend, Langenscheidt Pocket Hebrew Dictionary to the Old Testament (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969), 327.